Global Ecology

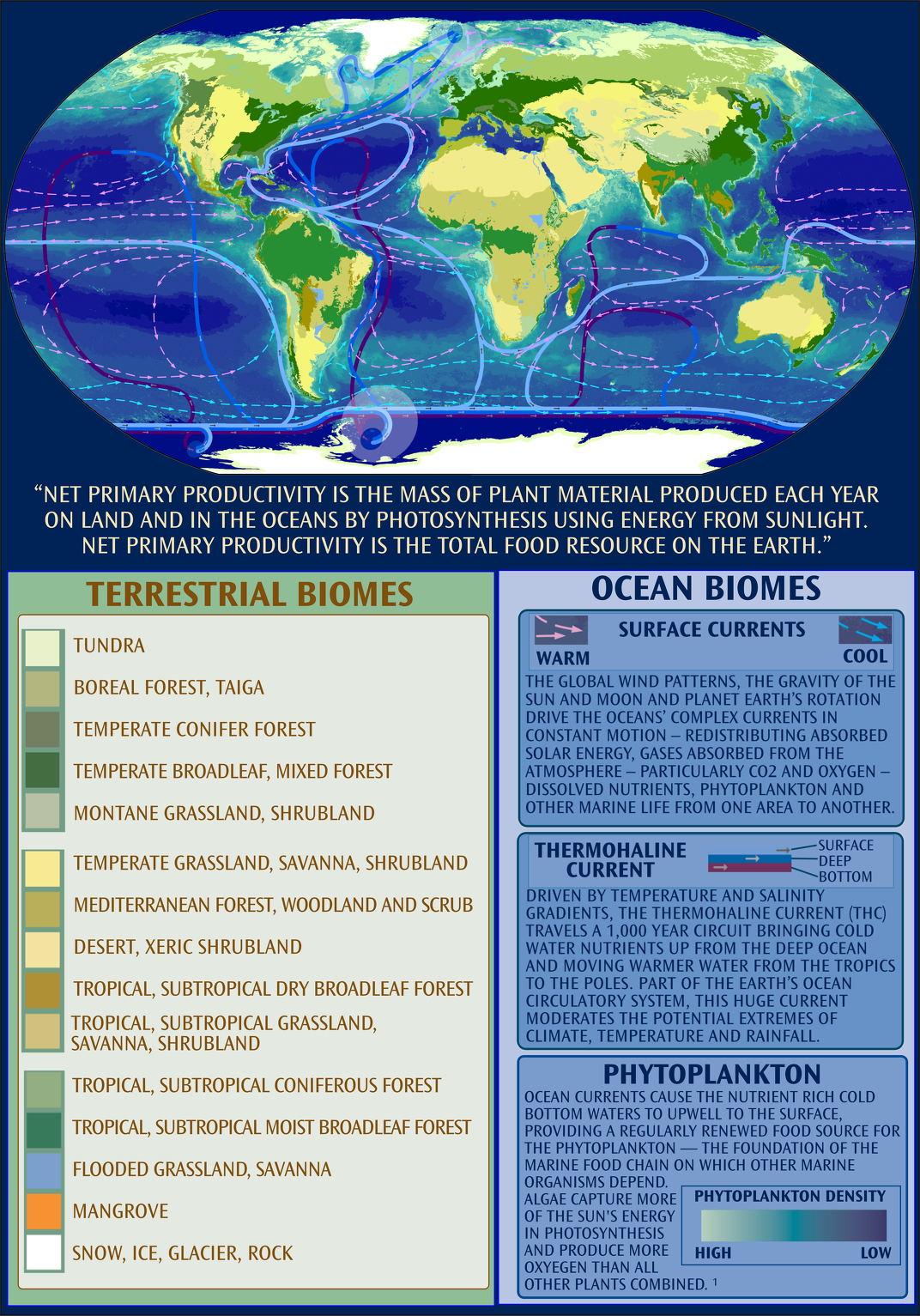

Population, pollution, greenhouse gases and deforestation are creating never before seen changes in Earth's living systems—including a cultural and species extinction rate that is the highest in the planet's history. Evidence is growing that the thermohaline circulation, driven by temperature and salinity, could be slowed or stopped by cold fresh water inputs to the Arctic and North Atlantic oceans, diluting the salt concentration in the ocean. This could occur if warming is sufficient to cause large scale melting of Arctic sea ice and the Greenland ice sheet. Such a change in the current may be gradual (over centuries) or very rapid (over a few years). Either would cause planet wide changes in climate. This effect may be part of what starts and stops the ice ages. The land in the Northern Hemisphere has been unfrozen for less than half of the last 400,000 years. In 2005, it was noted that the net flow of the thermohaline circulation had slowed by 30% between 1957 and 2004 (a short time frame relative to global events).

Evidence is growing that the thermohaline circulation, driven by temperature and salinity, could be slowed or stopped by cold fresh water inputs to the Arctic and North Atlantic oceans, diluting the salt concentration in the ocean. This could occur if warming is sufficient to cause large scale melting of Arctic sea ice and the Greenland ice sheet. Such a change in the current may be gradual (over centuries) or very rapid (over a few years). Either would cause planet wide changes in climate. This effect may be part of what starts and stops the ice ages. The land in the Northern Hemisphere has been unfrozen for less than half of the last 400,000 years. In 2005, it was noted that the net flow of the thermohaline circulation had slowed by 30% between 1957 and 2004 (a short time frame relative to global events).

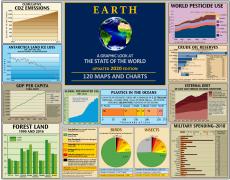

Directly or indirectly, the human species already captures nearly 40% of the total biological productivity on land and 70% of the productivity of the marine environment — the "net primary productivity" of the planet — for its exclusive use. The rate of increase in human use is about 2% per year."

Directly or indirectly, the human species already captures nearly 40% of the total biological productivity on land and 70% of the productivity of the marine environment — the "net primary productivity" of the planet — for its exclusive use. The rate of increase in human use is about 2% per year."The Biotic Crisis

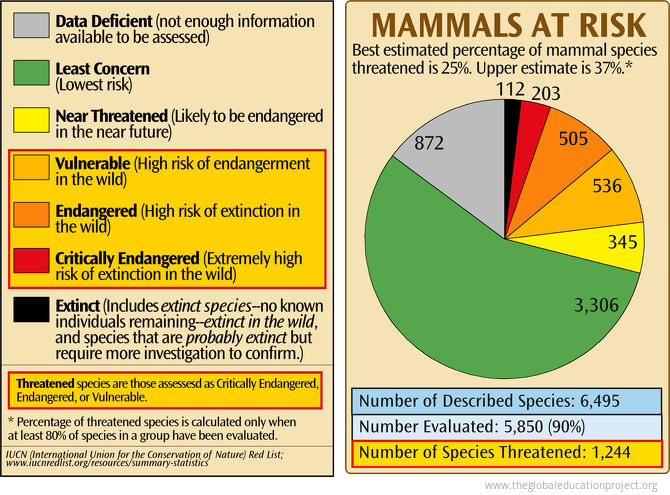

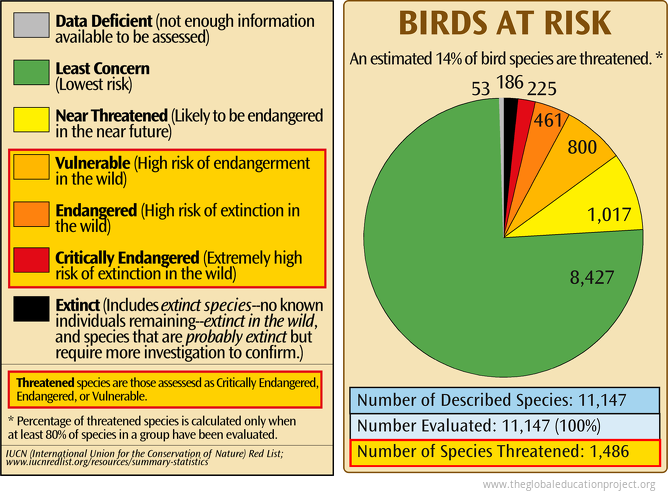

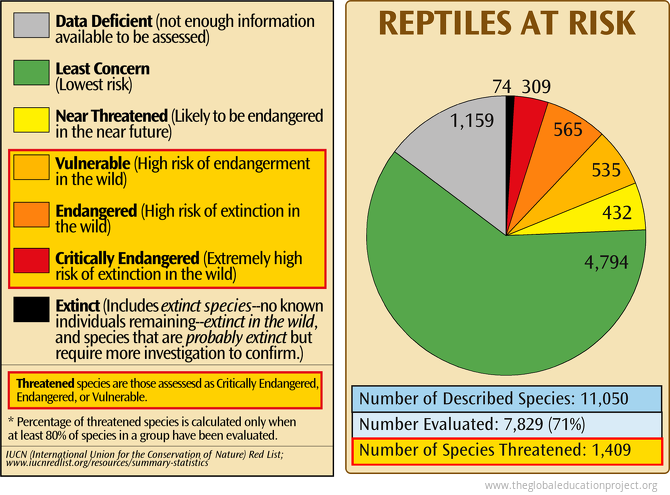

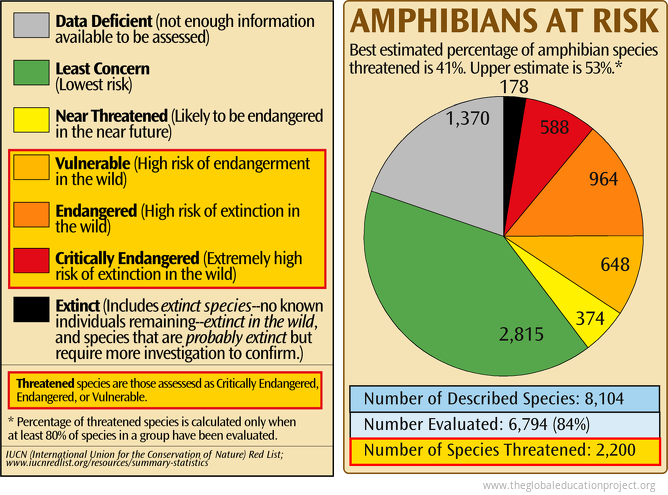

As a direct result of industrial civilization’s disruptive impact, planet earth has begun the 6th great biological extinction period in its 4.5 billion year history. During previous extinction events biodiversity was reduced by up to 70–90%. After past events, recovery took roughly 5 million years. However, the current depletion of biological diversity and, in particular, the prospect of severe depletion, if not virtual elimination of tropical forests, wetlands, estuaries and coral reefs that have been the “engines of biodiversity” for hundreds of millions of years, may have profound effects on the evolutionary processes that have previously fostered re-diversification. Even our largest protected areas will be far too small for the further speciation of large vertebrates. On the time scale of the human species, environmental disruption (or at least aspects of it) are permanent. [1]"An average of around 25 per cent of species in assessed animal and plant groups are threatened, suggesting that around 1 million species already face extinction.

"The global rate of species extinction... is already at least tens to hundreds of times higher than it has averaged over the past 10 million years.

"The direct drivers of change in nature with the largest global impact have been (starting with those with most impact): changes in land and sea use; direct exploitation of organisms; climate change; pollution; and invasion of alien species." [2]

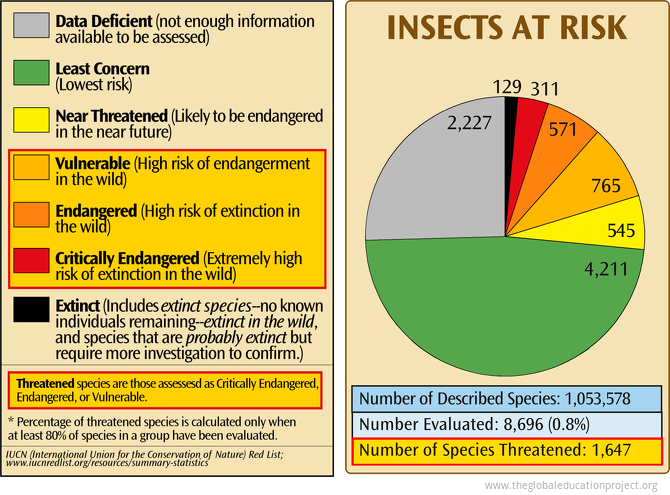

Insects play a central role in a variety of ecosystem processes, including: pollination, nutrient cycling and providing food sources for birds, mammals and amphibians. 80% of wild plants are estimated to depend on insects for pollination and 60% of birds rely on insects for food.

Insects play a central role in a variety of ecosystem processes, including: pollination, nutrient cycling and providing food sources for birds, mammals and amphibians. 80% of wild plants are estimated to depend on insects for pollination and 60% of birds rely on insects for food. In 2017, a German study found that flying insect populations in Europe have declined by over 75% in just 27 years. The IUCN assesses that over 9% of European bee species face extinction. Pollinators in particular face global threats that are driving decline, including: intensive agricultural practices, loss of habitat, pesticide use, and climate change.

Pesticides and Pollinators

In April 2021, a study of farmers’ self-reported use of 381 pesticides between 1992 and 2016, using data from the USGS and the US EPA, shows that despite the drop in their usage, the toxicity level of pesticides doubled for aquatic invertebrates such as plankton and insect larvae, and the same was true of important pollinators such as bees. This is largely a reflection of how pesticides have become stronger (therefore needing smaller applications), and newer products are designed to target particular pest species — although they do not distinguish between pests and potentially beneficial insects.The results challenge the claims that a decrease in pesticide use results in a decrease in environmental impacts.

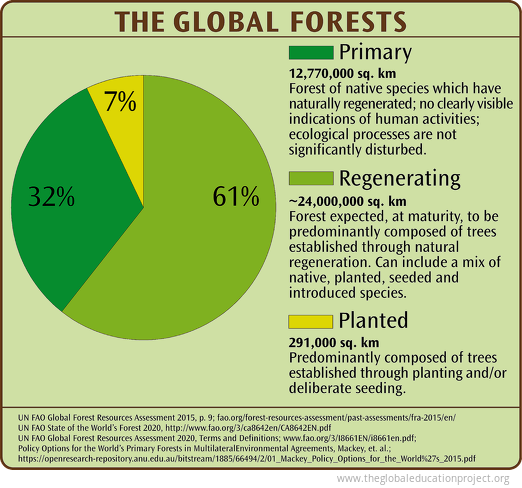

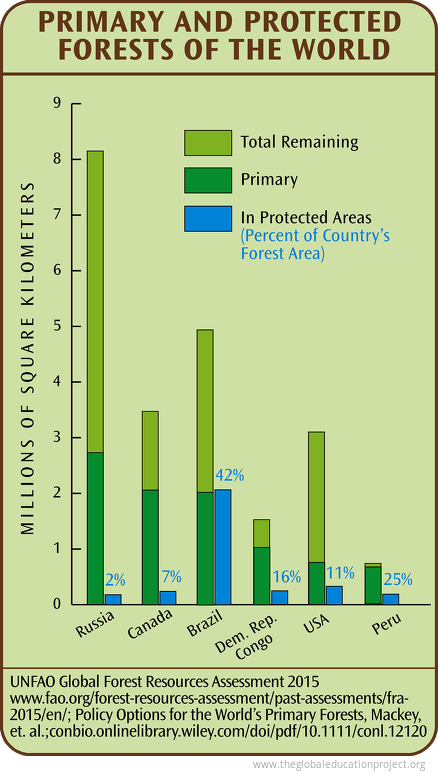

There are just under 40,000,000 sq. km of forest area remaining on Earth.

There are just under 40,000,000 sq. km of forest area remaining on Earth.Of the remaining primary forests, only ~18% are in legally protected forests, which is approximately 5% of the original forest estimated to have covered the planet 8,000 years ago.

The FAO defines primary forests as naturally regenerated forests of native tree species where there are no clearly visible indications of human activity and the ecological processes are not significantly disturbed.

While ‘old-growth’ is a commonly used term for primary forest, there is no generally agreed definition of old growth or age of trees because age varies with site, regional and biome specific factors. While many primary forest trees are long lived (300-1500 years), old growth is generally defined according to the presence of specific forest structures including large, older trees, snags, coarse woody debris and canopy layering that take decades to centuries to acquire.

Almost three quarters of Earth's remaining primary forests are in just ten countries. In addition to the countries shown in the above chart, there are only 0.46 million sq km in Indonesia, 0.45 in Venezuela, 0.36 in Bolivia, and 0.33 in Mexico.

Almost three quarters of Earth's remaining primary forests are in just ten countries. In addition to the countries shown in the above chart, there are only 0.46 million sq km in Indonesia, 0.45 in Venezuela, 0.36 in Bolivia, and 0.33 in Mexico.A large proportion of these forests occurs in contiguous blocks (500 sq. km or greater). Of these, 50% occur in polar regions, 46% in equatorial areas and 3% in warm temperate climatic zones.

10 to 25% of Earth’s remaining primary forest occurs in blocks that are smaller than 500 sq. km. These smaller areas of are of particular conservation significance in regions that are extensively cleared or fragmented. They function as refuges, intact ecosystems and sources of propagation for restoration.

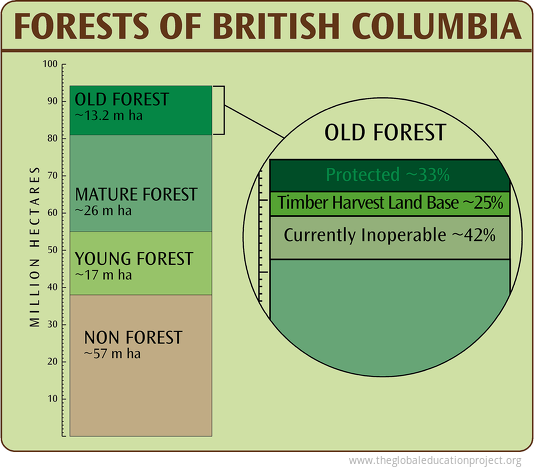

The area of British Columbia is about 95 million hectares. About 55% to 60% of the area is forest. (This precentage varies, depending on what is included; for example, federal land, Indian reserve, private land or water bodies.) Also counted as forest are areas that have been logged, burned, or damaged by insects, but are expected to regenerate. [1, 2]

The area of British Columbia is about 95 million hectares. About 55% to 60% of the area is forest. (This precentage varies, depending on what is included; for example, federal land, Indian reserve, private land or water bodies.) Also counted as forest are areas that have been logged, burned, or damaged by insects, but are expected to regenerate. [1, 2]Because the province has a diverse range of ecological and climate zones, the following categories, used for timber inventory purposes, are very broad and limited.

OLD FOREST (Forest with mostly old trees)

The provincial government’s official definition of old forest is based on the age of the dominant species in the stand (grouping of trees with similar characteristics). In general, this means 250 years or older on the coast, and 140 years or older in the interior.

In a 1992 management report, the province used a more ecologically focused definition: “Old growth forests are natural stands of old and young trees and their associated plants, animals, and ecological relationships which have remained essentially undisturbed by human activities”. [2, 6]

..."essentially undisturbed" can be taken to mean that there may be some evidence of human disturbance (such as historic Indigenous use or low-impact recreation trails, or removal of a few individual trees), but the ecosystem is functioning as if it had no human disturbance. These are widely used and accepted definitions in conservation and landscape ecology, but they are more challenging to measure and track, and cannot be directly correlated to the what is included in the 13.2 [million ha of old forest], even though there is likely a lot of overlap. [1]

MATURE FOREST (Forest with mostly mature trees)

These are stands that are considered biologically mature, but still too young to be counted as "old" according to the provincial criteria. For example, a Lodgepole Pine may be mature at 80 years but not considered old growth until it reaches the age of 140 years. [1, 2]

YOUNG FOREST (Forest with mostly young trees)

These are stands that are comprised mainly of trees lower than the age of maturity, including seedlings.

NON FOREST

These are ecosystems such as high alpine, water, non-treed grassland, rock, ice, desert – areas where trees generally do not or cannot grow. Included are previously forested areas that have been converted for urban development, infrastructure (roads, power lines, reservoirs, mines, valleys under dammed rivers), or agriculture. It is estimated that only 2 to 3% of BC’s original forests that existed 10,000 years ago have been converted, much of it in the past 200 years. However, some of these areas, such as the Fraser Valley, the largest estuary on the Pacific Coast, were of extreme ecological importance. [1, 4, 5]

PROTECTED FOREST

Of the 13.2 million ha of Old Forest, about 33% (4.4 million ha) is protected. "Protected" includes forest in parks, ecological reserves and wildlife management areas, ungulate winter range no-harvest areas, private conservation lands, regional water supply, OGMAs* (legal and non-legal Old Growth Management areas), and VQOs **(Visual Quality Objective). [1]

*OGMA: Areas that contain, or are managed to attain, specific structural old-growth attributes and that are delineated and mapped as fixed areas. [7] As stated in the BC data catalogue, “Forest licensees are not required to follow direction provided by non-legal OGMAs when preparing FSPs, and may choose to manage required old growth biodiversity targets in other ways.” [8]

**VQO: A program designed to manage the visual impacts on Crown forest land to ensure that the scenic quality expectations of the public and the tourism industry are met. [9]

TIMBER HARVEST LAND BASE (THLB)

Crown forest land that is considered both acceptable and economically feasible for harvesting. [7]

CURRENTLY INOPERABLE

Forest that is not currently considered economically feasible for harvesting.

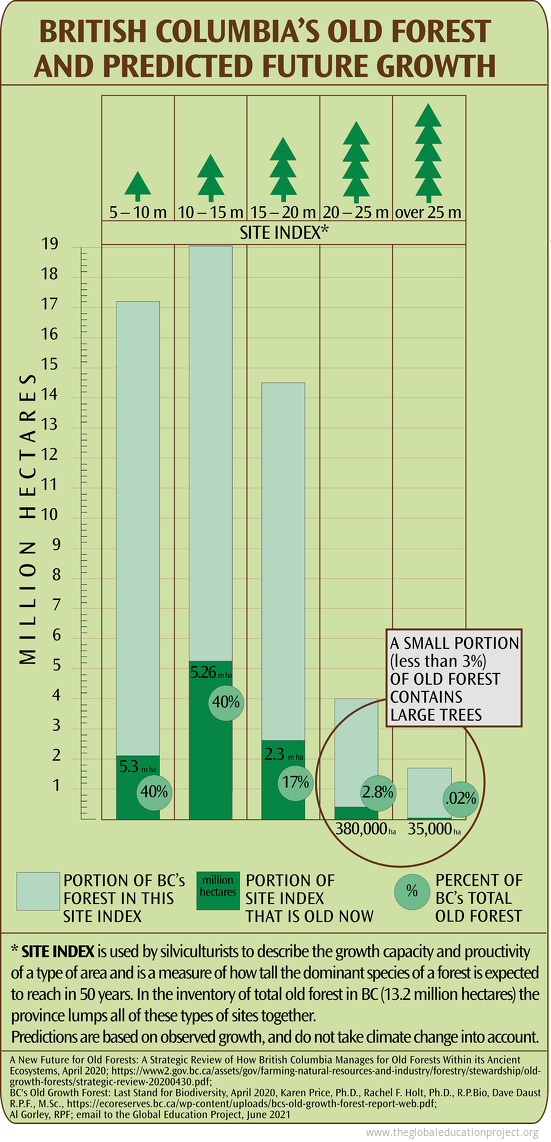

Forest areas with the potential to grow very large trees are extremely rare in Britsh Columbia. Old forests on these sites are almost extinguished and will not recover from logging.

Forest areas with the potential to grow very large trees are extremely rare in Britsh Columbia. Old forests on these sites are almost extinguished and will not recover from logging. "As much as 80% of the area of old forests consists of relatively small trees growing on lower productivity sites, such as Black Spruce bogs in the North, high elevation sub-alpine forests, or Cedar-Hemlock forests on the outer coast. Those forests remain in relatively great abundance,[the trees are small and are not currently considered economically feasible to harvest], and are important ecologically, but they are not what many people typically envision as 'old growth'"[1]

“These distinctions matter because while all forms of old growth have inherent value, different types provide tremendously different habitat, functional, cultural, spiritual and timber values. BC’s globally rare high productivity forests have particular value for their high biomass, structural complexity and stable carbon storage.” [2]

Ozone

Ozone gas in the upper atmosphere filters out the sun's ultraviolet rays and protects life forms from overexposure. This layer has been polluted by human activities and has developed thin areas or "holes" which let in more damaging levels of UV radiation. This in turn adversely affects many life forms—plants, animals and humans. Since 1989, the Montreal Protocol led to reductions in the atmospheric concentration of many ozone-depleting gases, such as CFCs, and ozone is projected to return to levels observed pre-1980 later this century. However, recent observations show the atmospheric concentration of dichloromethane—an ozone-depleting gas not controlled by the Montreal Protocol—is increasing rapidly and could delay the recovery of the ozone layer by up to 30 years. SPACE DEBRIS

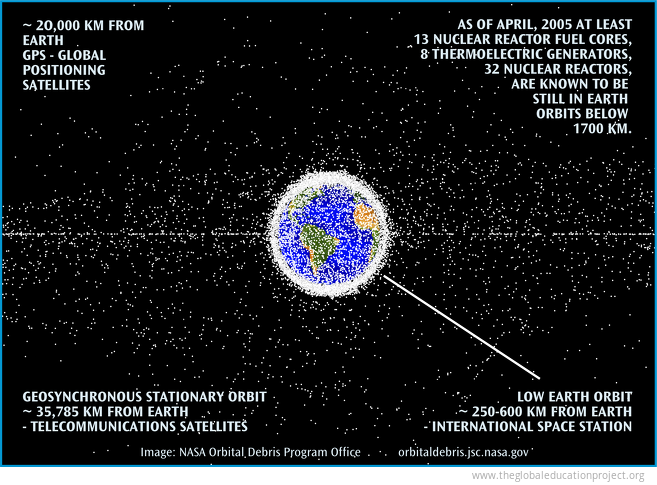

SPACE DEBRISBefore 1961, the entire Earth satellite population was just over 50 objects. Since 1957, about 9,600 satellites have been launched and about 5500 are still in space—and 2300 of these are still functioning. The total mass of all space objects in Earth's is more than 8800 tonnes.

Earth's orbit is now cluttered and dangerous with: ~34,000 objects bigger than 10 cm; ~ 900,000 objects from 1cm to 10 cm; and 128,000,000 objects from greater than 1 mm — 1 cm. However, the vast majority of space junk is too small to be tracked, and millions of tiny flecks zoom around Earth unseen by tracking instruments. "At 250 miles (400 km) up—the altitude of the International Space Station, which has had to maneuver away from three potential space-junk collisions in 2020 alone—objects barrel along at a blistering 17,500 mph (28,160 kph)."

What is it? Jettisoned mission junk, rocket fuel, space station garbage, abandoned rocket parts, used nuclear reactors, leaked radioactive coolant and exploded bits. To date, an estimated 500 break-ups, explosions, collisions, or anomalous events have occurred, making more debris.

As costs decrease the number of satellite launches increases—by 2025 as many as 1,100 satellites could be launched each year; up from 365 in 2018, and from 75 per year in 2005—and the chance of collisions increases.

In 2007, space debris mitigation guidelines were drawn up by the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee and the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. In September 2019, the newly established Space Station Coalition, a group of space-industry stakeholders, has recommended updated, voluntary guidelines of best practices. The US is responsible for the most debris in space, followed closely by Russia and China.

The commercial exploitation, militarization and weaponization of space around the earth is ongoing. Tourism is just getting started.

Sources

Terrestrial and Ocean Biomes Map:

Goddard Space Flight Center SeaWIFS data, gsfc.nasa.gov/topstory/20020801plankton.html;

Gaia, An Atlas of Planet Management; globalchange.umich.edu/globalchange2/current/ lectures/fisheries/fisheries.htm; Ecosystem and Biodiversity

Text Source: Environmental Research Foundation, ejnet.org/rachel/rhwn256.htm

Christian Science Monitor, “Tiniest Creatures in the World Reveal Health of Oceans”

Slowing of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation at 25° N. Nature 438, 655–657 (2005), Bryden, H., Longworth, H. & Cunningham, S. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04385

Antarctic Geography, Ice, and Currents Map:

"Antarctic Region"; Perry Castaneda Map Library, www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/; National Snow and Ice Data Center, http://nsidc.org; National Geographic Maps, "Antarctica", Feb. 2002

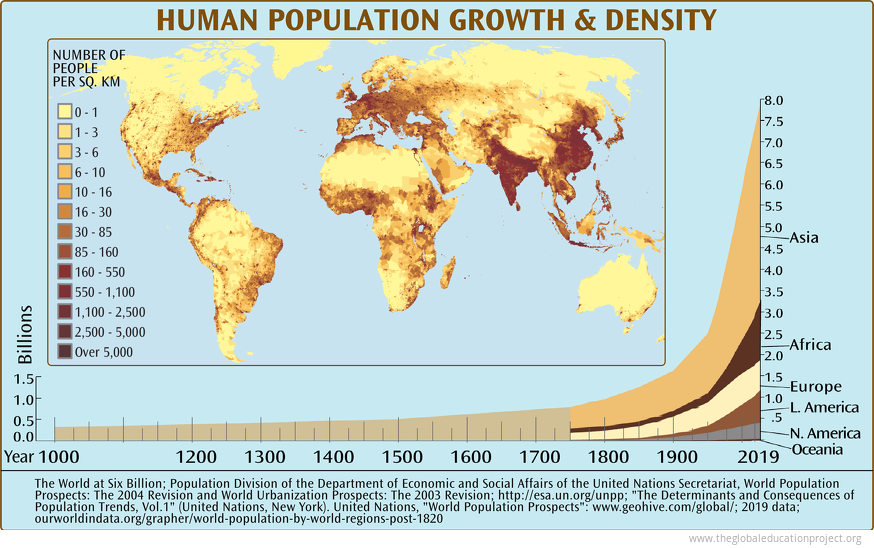

Human Population Growth by Region Chart:

Environmental Research Foundation, www.ejnet.org/rachel/rhwn256.htm

Map Data Source: Center for International Earth Science Information Network, Columbia University, “Grided Population of the World”

Text: UNESCO World Water Assessment Programme, Office for Global Water Assessment; www.unesco.org/water/wwap

The Biotic Crisis Text:

1. The Biotic Crisis and the Future of Evolution, PNAS - pnas.org/cgi/content/full/98/10/5389

2. Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), 2019 Global Assessment Report; http://www.ipbes.net/

Mammals at Risk of Extinction Chart:

Charts: International Union for the Conservation of Nature: Red List of Threatened Species; https://www.iucn.org/resources/conservation-tools/iucn-red-list-threatened-species

Birds at Risk of Extinction Chart:

Charts: International Union for the Conservation of Nature: Red List of Threatened Species; https://www.iucn.org/resources/conservation-tools/iucn-red-list-threatened-species

Reptiles at Risk of Extinction Chart:

Charts: International Union for the Conservation of Nature: Red List of Threatened Species; https://www.iucn.org/resources/conservation-tools/iucn-red-list-threatened-species

Amphibians at Risk of Extinction Chart:

Charts: International Union for the Conservation of Nature: Red List of Threatened Species; https://www.iucn.org/resources/conservation-tools/iucn-red-list-threatened-species

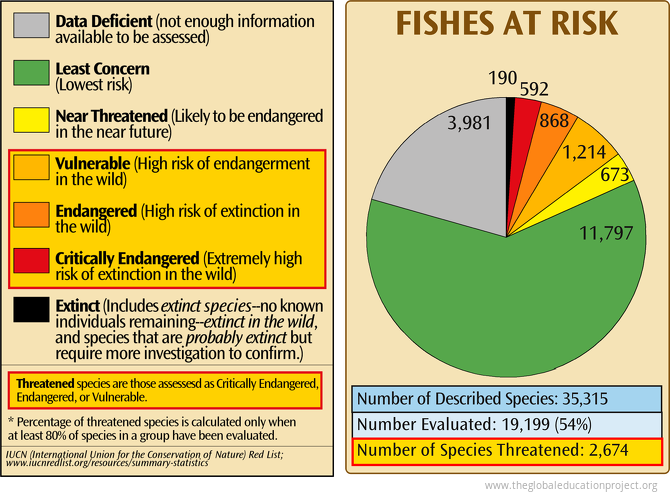

Fishes at Risk of Extinction Chart:

Charts: International Union for the Conservation of Nature: Red List of Threatened Species; https://www.iucn.org/resources/conservation-tools/iucn-red-list-threatened-species

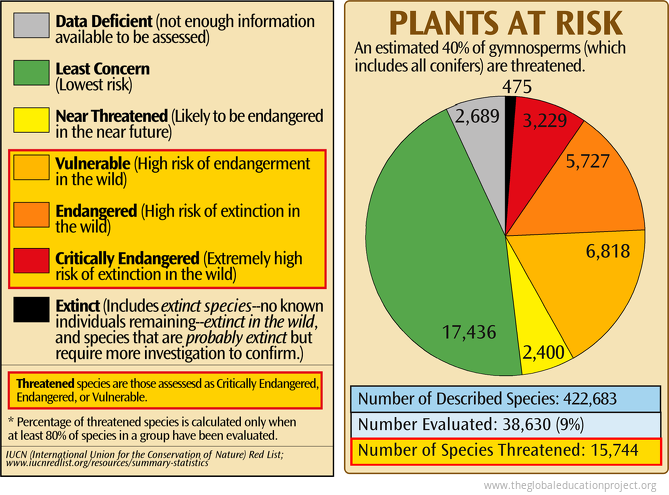

Plants at Risk of Extinction Chart:

Charts: International Union for the Conservation of Nature: Red List of Threatened Species; https://www.iucn.org/resources/conservation-tools/iucn-red-list-threatened-species

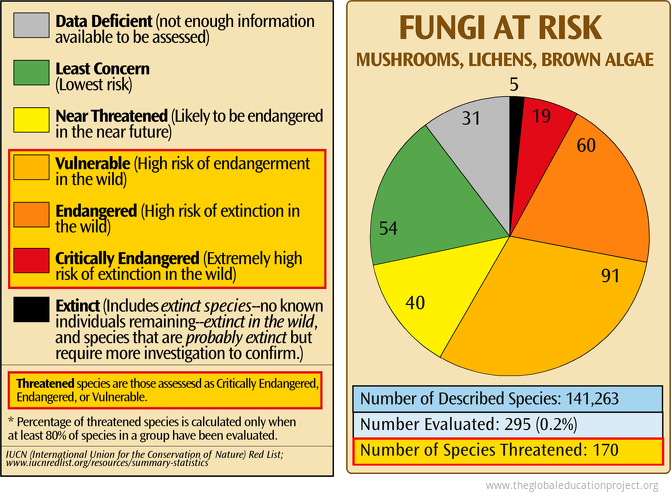

Fungi at Risk of Extinction Chart:

Charts: International Union for the Conservation of Nature: Red List of Threatened Species; https://www.iucn.org/resources/conservation-tools/iucn-red-list-threatened-species

Insects at Risk of Extinction Chart:

Charts: International Union for the Conservation of Nature: Red List of Threatened Species; https://www.iucn.org/resources/conservation-tools/iucn-red-list-threatened-species;

Text:"Pollinators in Europe"; iucn.org/regions/europe/our-work/pollinators-europe; "More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas"; PLoS ONE. 12. 1-21. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185809.

Pesticides and Pollinators Text:

"Applied pesticide toxicity shifts toward plants and invertebrates, even in GM crops",

Schulz, Ralf, et al.; Science 02 Apr 2021, DOI: 10.1126/science.abe1148

"US Pesticide Use Is Down, but Damage to Pollinators Is Rising", The Scientist, April 5, 2021, www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/us-pesticide-use-is-down-but-damage-to-pollinators-is-rising-68635

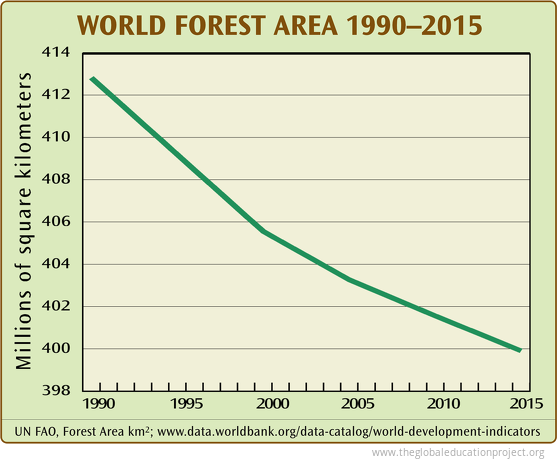

World Forest Area 1990 - 2015 Chart:

UN FAO, Forest Area km2; data.worldbank.org

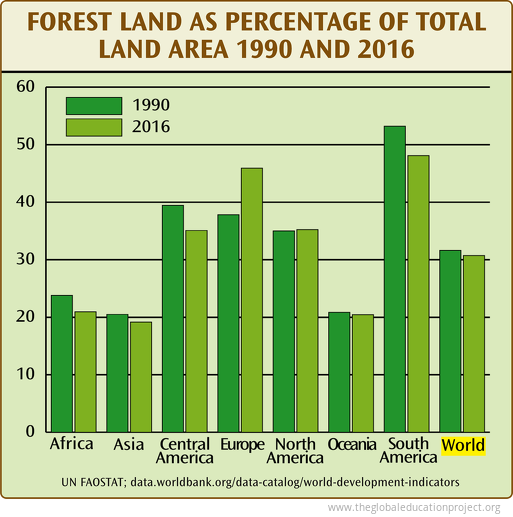

Forest Land As Percentage of Total Land Area 1990 and 2016 Chart:

UN FAOSTAT; data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators

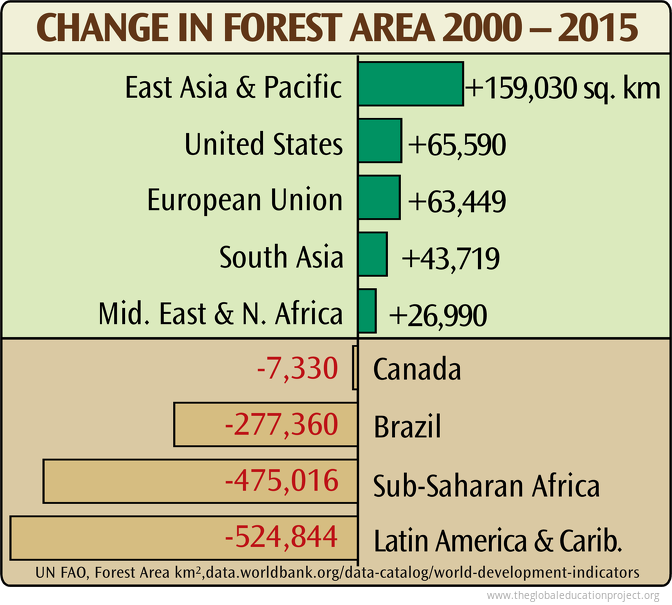

Change in Forest Area by Region Chart:

UN FAO, Forest Area km2; data.worldbank.org

Global Forest Chart:

UN FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015, p. 9; fao.org/forest-resources-assessment/past-assessments/fra-2015/en/

UN FAO State of the World’s Forest 2020, http://www.fao.org/3/ca8642en/CA8642EN.pdf

UN FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020, Terms and Definitions; www.fao.org/3/I8661EN/i8661en.pdf;

Policy Options for the World’s Primary Forests in MultilateralEnvironmental Agreements, Mackey, et. al.;

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/66494/2/01_Mackey_Policy_Options_for_the_World%27s_2015.pdf

Text source: https://primaryforest.org/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-1-primary-forrest-introduction/

Primary and Protected Forests Chart:

UNFAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015

www.fao.org/forest-resources-assessment/past-assessments/fra-2015/en/

Policy Options for the World’s Primary Forests, Mackey, et. al.;

conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/conl.12120

Forests of British Columbia Chart:

1. Al Gorley, RPF; email to the Global Education Project, June 2021

2. A New Future for Old Forests: A Strategic Review of How British Columbia Manages for Old Forests Within its Ancient Ecosystems, April 2020; https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/farming-natural-resources-and-industry/forestry/stewardship/old-growth-forests/strategic-review-20200430.pdf

3. BC's Old Growth Forest: Last Stand for Biodiversity

April 2020, Karen Price, Ph.D., Rachel F. Holt, Ph.D., R.P.Bio and Dave Daust R.P.F., M.Sc., Veridian Ecological Consulting; https://ecoreserves.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/bcs-old-growth-forest-report-web.pdf

4. Rachel Holt, Ph.D; email to the Global Education Project, June 2021

5. “British Columbia’s Forests and Their Management”, Sept. 2003,

https://www.for.gov.bc.ca/hfd/pubs/Docs/Mr/Mr113/index.htm

6. “An Old Growth Strategy for British Columbia”, BC Ministry of Forests, May 1992

7. Glossary Of Terms By BC Forest Practices Board, https://www.bcfpb.ca/news-resources/glossary/

8. BC Data Catalogue, Old Growth Management Areas, https://catalogue.data.gov.bc.ca/dataset/old-growth-management-areas-non-legal-all

9. Visual Resource Management, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/forestry/managing-our-forest-resources/visual-resource-management

Old Forests of British Columbia Chart:

1. A New Future for Old Forests: A Strategic Review of How British Columbia Manages for Old Forests Within its Ancient Ecosystems, April 2020; https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/farming-natural-resources-and-industry/forestry/stewardship/old-growth-forests/strategic-review-20200430.pdf;

2. BC's Old Growth Forest: Last Stand for Biodiversity, April 2020, Karen Price, Ph.D., Rachel F. Holt, Ph.D., R.P.Bio and Dave Daust R.P.F., M.Sc., Veridian Ecological Consulting; https://ecoreserves.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/bcs-old-growth-forest-report-web.pdf;

Al Gorley, RPF; email to the Global Education Project, June 2021

Ozone Text:

"The increasing threat to stratospheric ozone from dichloromethane", Hossaini, R., Chipperfield, M., Montzka, S. et al, (2017); https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15962

Space Debris Image:

Image: NASA Orbital Debris Program Office, orbitaldebris.jsc.nasa.gov

*Approximately 95% of the objects in this computer generated illustration are orbital debris, i.e., not functional satellites. The dots represent the current location of each item and are scaled to optimize their visibility and are not scaled to Earth.

Text: European Space Agency, www.esa.int/Safety_Security/Space_Debris/Space_debris_by_the_numbers; Space.com, www.space.com/space-junk; "MIT Technology Review", www.technologyreview.com/2019/06/26/755/satellite-constellations-orbiting-earth-quintuple/; "Best Practices for the Sustainability of Space Operations." https://spacesafety.org/

Tags: global ecology

Sign up for EARTH Dispatches

Enter you email below to get jaw dropping charts and maps delivered straight to your inbox.

Get the EARTH presentation

A 150 page high-resolution PDF containing all updated maps, charts and data on EARTH website; use as an information-packed educational slide show, printed booklet or a set of single-page handouts.

Learn More