Advanced Machining in Ancient Egypt Page 8

By Christopher P. Dunn

These artifacts need to be thoroughly mapped and inspected with the following tools.

1. A laser interferometer with surface flatness checking capabilities

2. An ultrasonic thickness gage to check the thickness of the walls to determine their consistency to uniform thickness.

3. An optical flat with monochromatic light source. Are the surfaces really finished to optical precision?

With Eric Leither of Tru-Stone Corp, I discussed in a letter the technical feasibility of creating several Egyptian artifacts,

including the giant granite boxes found in the bedrock tunnels the temple of Serapeum at Saqqarra. He responded as follows.

"Dear Christopher,

First I would like to thank you for providing me with all the fascinating information. Most people never get the

opportunity to take part in something like this.

You mentioned to me that the box was derived from one solid block of granite. A piece of granite of that size is

estimated to weigh 200,000 pounds if it was Sierra White granite which weighs approximately 175 lb. per cubic foot.

If a piece of that size was available, the cost would be enormous. Just the raw piece of rock would cost somewhere in

the area of $115,000.00. This price does not include cutting the block to size or any freight charges.

The next obvious problem would be the transportation. There would be many special permits issued by the D.O.T.

and would cost thousands of dollars. From the information that I gathered from your fax, the Egyptians moved this

piece of granite nearly 500 miles. That is an incredible achievement for a society that existed hundreds of years

ago.."

Eric went on to say that his company did not have the equipment or capabilities to produce the boxes in this manner. He said

that his company would create the boxes in 5 pieces, ship them to the customer, and bolt them together on site.

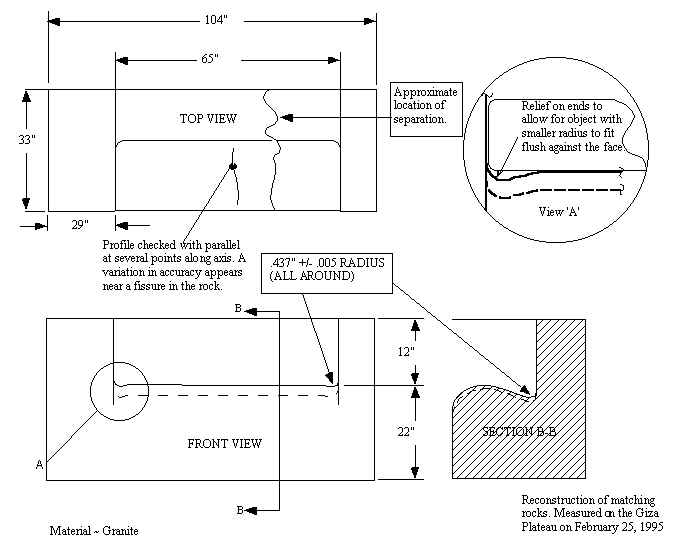

The final artifact I inspected was a piece of granite I quite literally stumbled across while strolling around the Giza Plateau later

that day. I concluded, after doing a preliminary check of this piece, that the ancient pyramid builders had to have used a

three-axes machine to guide the tool that created it. Outside of being incredibly precise, normal flat surfaces, being simple

geometry, can justifiably be explained away by simple methods. This piece, though, drives us beyond the question normally

pondered - "what tools were used to cut it?" - to a more far reaching question.. - "what guided the cutting tool?"

In answering this question, and being comfortable with the answer, it is helpful to have a working knowledge of contour

machining.

Many of the artifacts that modern civilization produces would be impossible to produce using simple hand work. We are

surrounded by artifacts that are the result of men and women employing their minds to create tools which overcome their

physical limitations. We have developed machine tools to create the dies that produce the aesthetic contours on the cars that

we drive, the radios we listen to and the appliances we use.

To create the dies to produce these items, a cutting tool has to accurately and consistently follow a predetermined contoured

path in three dimensions. In some applications it will move in three dimensions, simultaneously using three or more axes of

movement. The artifact that I was looking at required a minimum of three axes to machine it. When the machine tool industry

was relatively young, techniques were employed where the final shape was finished by hand, using templates as a guide.

Today, with the use of precision computer numerical control machines, there is little call for hand work. A little polishing to

remove unwanted tool marks may be the only hand work required. To know that a piece has been produced on such a

machine, therefore, one would expect to see a precise surface with indications of tool marks that show the path of the tool.

This is what I found on the Giza Plateau, laying out in the open south of the Great Pyramid about 100 yards east of the second

pyramid.

There are so many rocks of all shapes and sizes lying around this area to the untrained eye, this one could easily be

overlooked. To a trained eye, it may attract some cursory attention and a brief muse. I was fortunate that it both caught my

attention, and that I had the tools with which to inspect it.

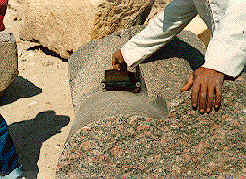

There were two pieces laying close together, one larger than the other. They had originally been one piece and had been

broken. With the exception of my broken indicator gage, I found I needed every tool that I had brought with me to inspect it.

In inspecting this piece, I was interested in the accuracy of the contour and its symmetry.

Contoured Block of Granite - Giza

What we have is an object that, three dimensionally as one piece, could be likened to a small sofa. The seat is a contour that

blends into the walls of the arms and the back. The contour was checked using the profile gage along three axes of its length,

starting at the blend radius near the back, and ending near the tangency point, which blended smoothly where the contour

radius meets the front. The wire radius gage is not the best way to determine the accuracy of this piece. When adjusting the

wires at one position on the block and moving to another position, the gage could be re-seated on the contour, but questions

could be raised as to whether the hand that positioned it compensated for some inaccuracy in the contour. However, placing

the parallel at several points along and around the axes of the contour, I found the surface to be extremely precise. At one

point near a crack in the piece, there was light showing through, but the rest of the piece allowed very little to show.

During this time, I had attracted quite a crowd. It’s difficult to traverse the Giza Plateau at the best of times without getting

attention from the camel drivers, the donkey riders and the purveyors of trinkets. It wasn’t long after I had pulled the tools out

of my back-pack that I had two willing helpers, Mohammed and Mustapha, who weren’t at all interested in compensation. At

least that’s what they told me. But I can honestly say that I lost my shirt on that adventure. I had cleaned sand and dirt out of

the corner of the larger block and washed it out with water. I used a white T-shirt that I was carrying in my back-pack to

wipe the corner out so I could get an impression of it with forming wax. Mustapha, talked me into giving him the shirt before I

left. I was so inspired by what I had found I tossed it to him.

Mohammed held the wire gage at different points along the contour while I took photographs of it. I then took the forming

wax and heated it with a match, kindly provided by the Movenpick hotel, then pressed it into the corner blend radius. I then shaved off the splayed part and positioned it at different points around. Mohammed held the wax still

while I took photographs. By this time there was an old camel driver and a policeman on a horse looking on.

Location where the wax impression was taken.

Verifying the radius at another location

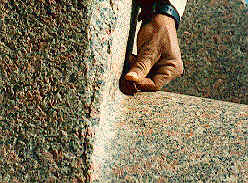

What I discovered with the wax was a uniform radius, tangential with the contour and the back and side walls. Returning to

the US, I measured the wax and found, using a radius gage, that it was a true radius and measured 7/16 inch.

The side arm blend radius has a design feature that is common engineering practice today. By cutting a relief at the corner, a

mating part that is to match, or butt up against the surface with the large blend radius, may have a smaller radius. This feature

provides for a more efficient operation because it allows a cutting tool with a large diameter, and, therefore, a large radius, to

be used. With greater rigidity in the tool, more material can be removed when taking a cut.

I believe there is more, much more, that can be gleaned using these methods of study. The Cairo Museum contains many

artifacts that will reveal much the same conclusion that I’m presenting in this paper. In terms of a more thorough understanding

of the level of technology employed by the ancient pyramid builders, the implications of these discoveries are tremendous. We

are not only presented with hard evidence that seems to have eluded us for decades and which provides further evidence

proving the ancients to be advanced, we are also provided with an opportunity to re-analyze everything with a different

perspective, from a different angle. Understanding how something is made opens up a different dimension when trying to

determine why it was made.

The precision in these artifacts is irrefutable. Even if we ignore the question of how they were produced, we are still faced with

the question of why such precision was needed. The implications of this question are just as profound.

|