Advanced Machining in Ancient Egypt Page 7

By Christopher P. Dunn

I had followed Graham and Robert on their trip to this site for a filming on Feb. 24, 1995. We were in the stifling atmosphere

of the tunnels, where dust kicked up from tourists lay heavily in the still air. These tunnels contain 21 huge granite boxes. Each

box weighs an estimated 65 tons, and, together with the huge lid that sits on top of them, the total weight of the assembly is

around 100 tons. Just inside the entrance of the tunnels there is a lid that had not been finished and beyond this lid, barely

fitting within the confines of one of the tunnels, is a granite box that had also been rough hewn.

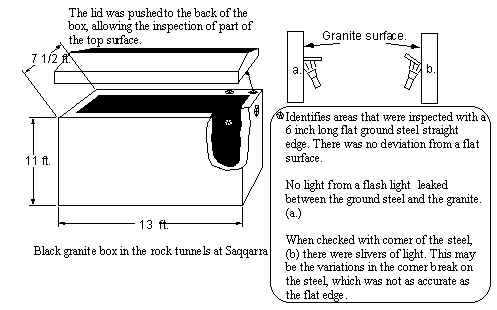

The granite boxes are 13 ft. long, 7 1/2 ft. wide and 11 ft. high. They are installed in "crypts" that were hewn out of the

limestone bedrock at staggered intervals along the tunnels. The floors of the crypts were about 4 ft. below the tunnel floor, and

the boxes were set into a recess in the center. Robert Bauvall was addressing the engineering aspects of installing such huge

boxes within a confined space where the last crypt was located near the end of the tunnel; a dead end with no room for the

hundreds of slaves pulling on ropes, according to theories proposed by those who believe that the ancient pyramid builders

were a primitive society.

While Graham and Robert were filming, I jumped down into a crypt and placed my parallel against the outside surface of the

box. It was perfectly flat. I shone the flashlight and found no deviation from a perfectly flat surface. I clambered through a

broken out edge into the inside of another giant box and again, I was astonished to find it astoundedly flat. I looked for errors

and couldn’t find any. I wished at that time that I had the proper equipment to scan the entire surface and ascertain the full

scope of the work. Nonetheless, I was perfectly happy to use my flashlight and straight edge and stand in awe of this

incredibly precise and incredibly huge artifact. Checking the lid and the surface on which it sat, I found them both to be

perfectly flat. It occurred to me that this gave the manufacturers of this piece a perfect seal. Two perfectly flat surfaces

pressed together, with the weight of one pushing out the air between the two surfaces! The technical difficulties in finishing the

inside of this piece made the sarcophagus in Khafra’s pyramid seem like a walk in the park.

I was accompanied by Canadian researcher Robert McKenty at this time. He saw the significance of the discovery and was

filming with his camera. At that moment I knew how Howard Carter must have felt when he discovered Tutenkahmen’s tomb.

I yelled for Graham and Robert to share the discovery, but was denied their presence by Roel Oostra, who was working to a

tight schedule and had to complete his filming.

The dust filled atmosphere in the tunnels was extremely unhealthy. I could only imagine what it would be like if I was finishing

off a piece of granite, regardless of what method I used, how unhealthy it would be. Surely it would have been better to finish

the work in the open air? I was so astonished by this find that it didn’t occur to me until later that the builders of these relics,

for some esoteric reason, intended for them to be ultra precise. They had taken the trouble to bring into the tunnel the

unfinished product and finish it underground for a good reason! It is the logical thing to do if you require a high degree of

precision in the piece that you are working. To finish it with such precision at a site that maintained a different atmosphere and

a different temperature, such as in the open under the hot sun, would mean that when it was finally installed in the cool,

cave-like temperatures of the tunnel, you would lose that precision. The granite would change its shape, or creep. The

solution, of course, was to prepare the precision surfaces in the location in which they were going to be housed.

This discovery, and the realization of its critical importance to the artisans that built it, went beyond my wildest dreams of

discoveries to be made in Egypt. For a man of my inclination, this was better than King Tut’s tomb.

The Egyptians’ intentions with respect to precision is perfectly clear. But for what purpose? In America today, the cost of just

the quarried granite would be $115,000.00. That’s without shipping costs and manufacturing costs, assuming there was

equipment available to machine it. I have contacted four precision granite manufacturers in the US and haven’t been able to

find one who can do this kind of work.

|